Biography & Research Overview

Michael Hendzel's laboratory is an internationally recognized leader in the study of the cell nucleus, chromatin structure, and genome stability. The lab's research program is driven by fundamental questions about how our DNA is organized, packaged, maintained, and repaired. A unique strength of the Hendzel lab is its deeply interdisciplinary approach, which seamlessly integrates cell biology, biophysics, and radiation biology to probe the innermost workings of the cell.

The group has made pioneering contributions to the field, including the paradigm-shifting discovery that chromatin, the complex of DNA and protein, behaves like a gel rather than a liquid inside the nucleus. Such findings challenge textbook models and open entirely new avenues for cancer research. By focusing on how these fundamental nuclear processes can be understood and manipulated for therapeutic benefit, the Hendzel lab continues to push the frontiers of genome biology.

Research Focus

Genome Stability Mechanisms

The team investigates the complex safeguards that ensure the faithful inheritance of genetic material during cell division. Using advanced single-cell imaging techniques, they observe how cells respond to and cope with DNA damage in real time.

DNA Double-Strand Break Repair

The lab is particularly interested in how a cell chooses between different pathways to repair these highly toxic lesions. They made a breakthrough discovery by identifying the enzyme RNF138 as a key factor that removes a barrier protein from broken DNA ends, thereby promoting the most accurate form of repair.

Chromatin Dynamics & Epigenetic Regulation

This research explores how the physical and chemical state of chromatin affects gene activity and DNA repair. Their landmark finding that chromatin exists in a gel-like state has profound implications for understanding how molecules move within the nucleus and access the genome.

Nuclear Organization

Investigation of how the cell nucleus is organized and how this organization affects DNA repair, gene expression, and cellular function. This work aims to lay the foundation for epigenetic therapies that could make cancer cells more vulnerable to treatment.

Research Highlights

Recent breakthrough discoveries from the Hendzel Laboratory advancing our understanding of nuclear biology, chromatin structure, and genome stability.

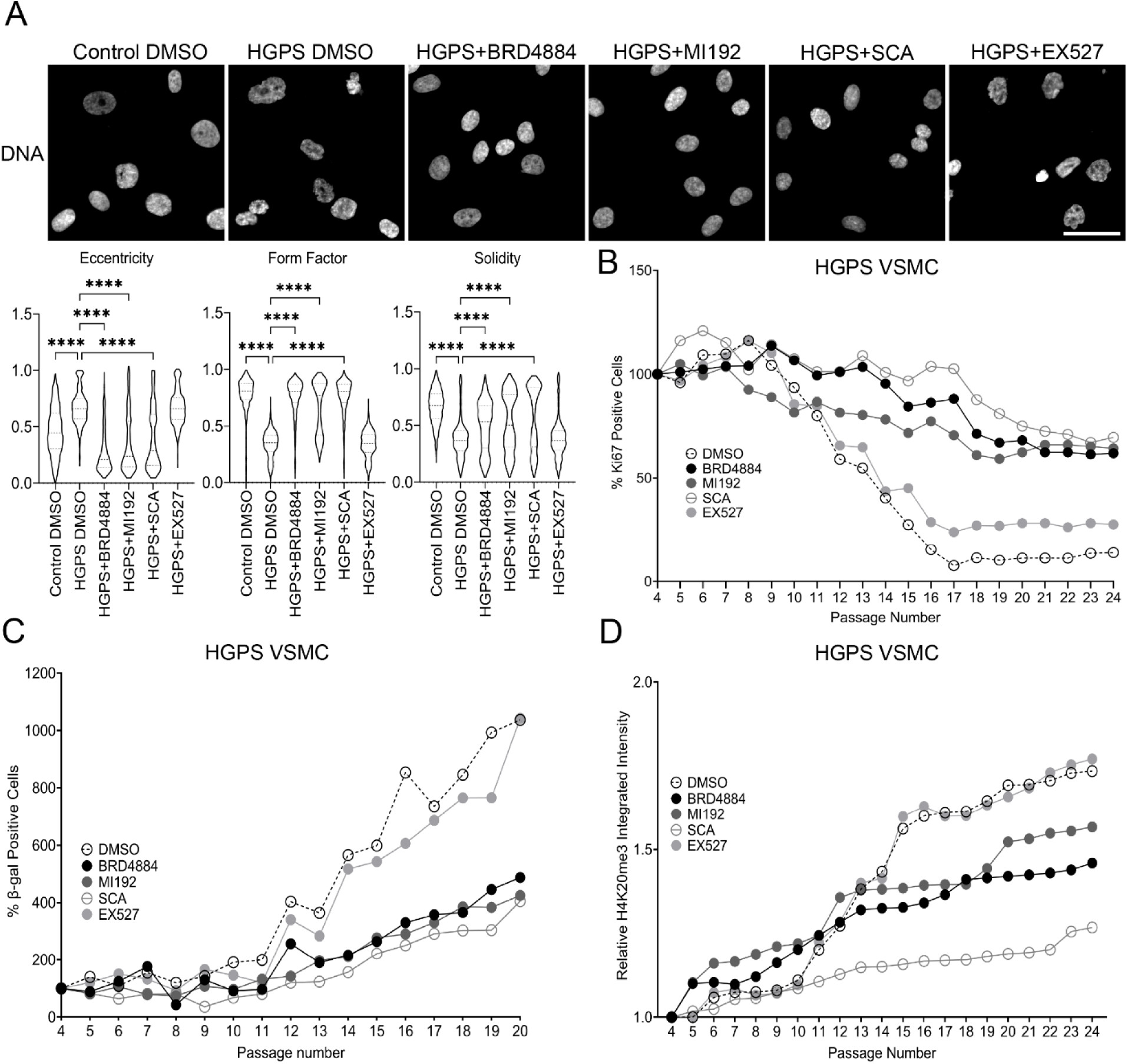

Therapeutic Rescue of Progeria via HDAC2 Inhibition

Karimpour et al.

Significance: Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS) is a devastating premature aging disorder caused by accumulation of the toxic protein progerin. This groundbreaking study reveals that HDAC2 (histone deacetylase 2) plays a central role in progerin toxicity. Progerin directly interacts with HDAC2, hijacking it to disrupt normal chromatin structure and gene regulation.

Most remarkably, we demonstrated that pharmacological inhibition of HDAC2 rescues multiple cellular defects in progeria cells, including restoration of normal nuclear morphology, reduction of DNA damage, and normalization of heterochromatin markers. This work identifies HDAC2 as a promising therapeutic target and provides proof-of-concept that small molecule inhibitors could potentially treat this currently incurable disease. The findings also have broader implications for understanding normal aging processes, as progerin accumulates at low levels during physiological aging.

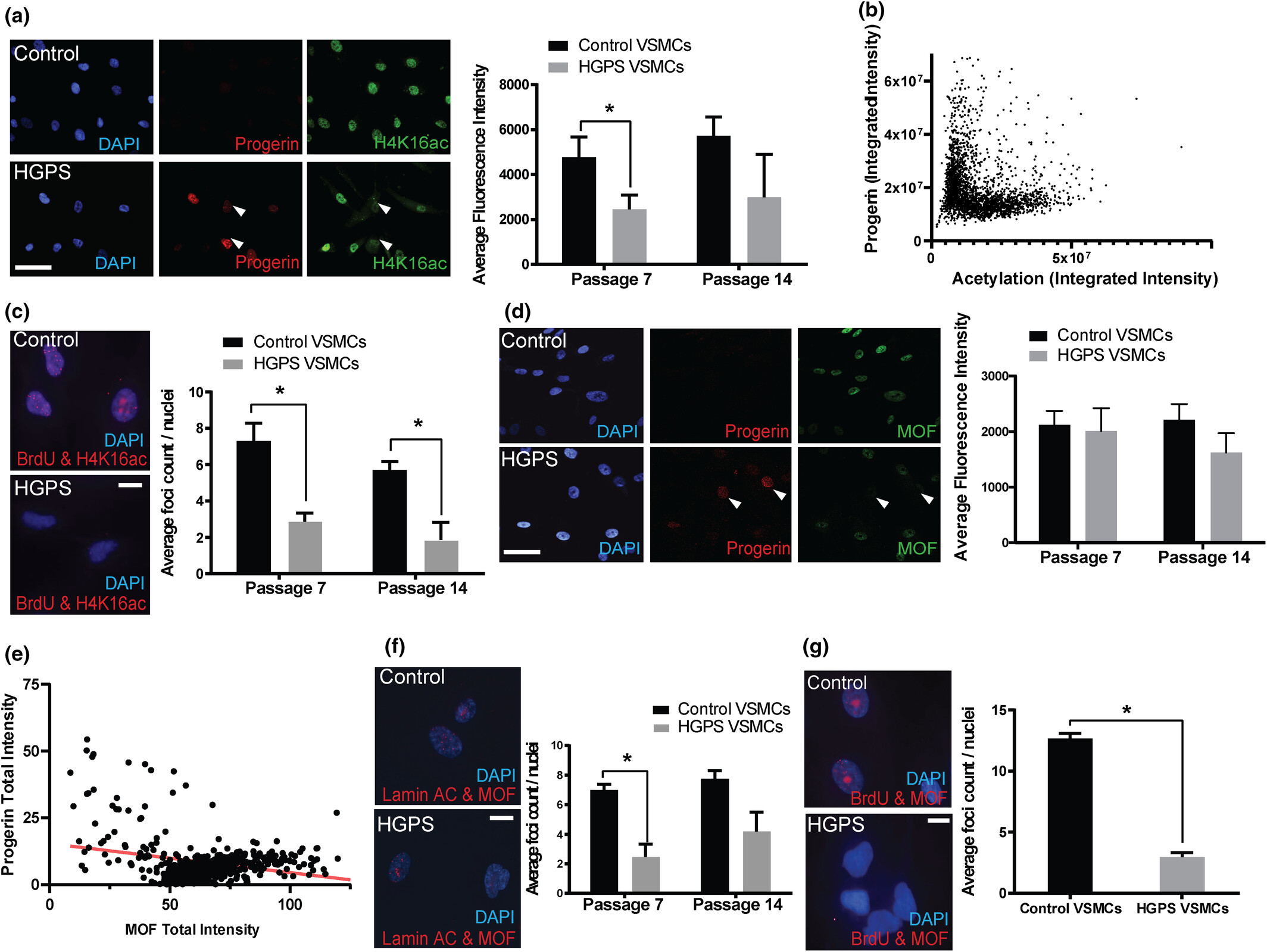

Mechanisms of Vascular Aging in Progeria: Loss of Epigenetic Homeostasis in Vascular Smooth Muscle Cells

Ngubo et al.

Significance: Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in Hutchinson-Gilford Progeria Syndrome (HGPS), yet the molecular mechanisms underlying vascular pathology have remained poorly understood. This comprehensive study reveals that vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) from progeria patients undergo profound epigenetic changes that drive premature cellular senescence.

Using patient-derived cells and sophisticated imaging techniques including super-resolution microscopy, we discovered that progerin expression leads to loss of key heterochromatin marks (H4K16ac) and chromatin architectural proteins (MOF), resulting in accelerated senescence and impaired VSMC function. Remarkably, these epigenetic defects mirror those observed during normal vascular aging, but occur at a dramatically accelerated rate in progeria. This work establishes progeria as a powerful model for understanding physiological vascular aging and identifies specific epigenetic pathways as potential therapeutic targets for both progeria and age-related cardiovascular disease.

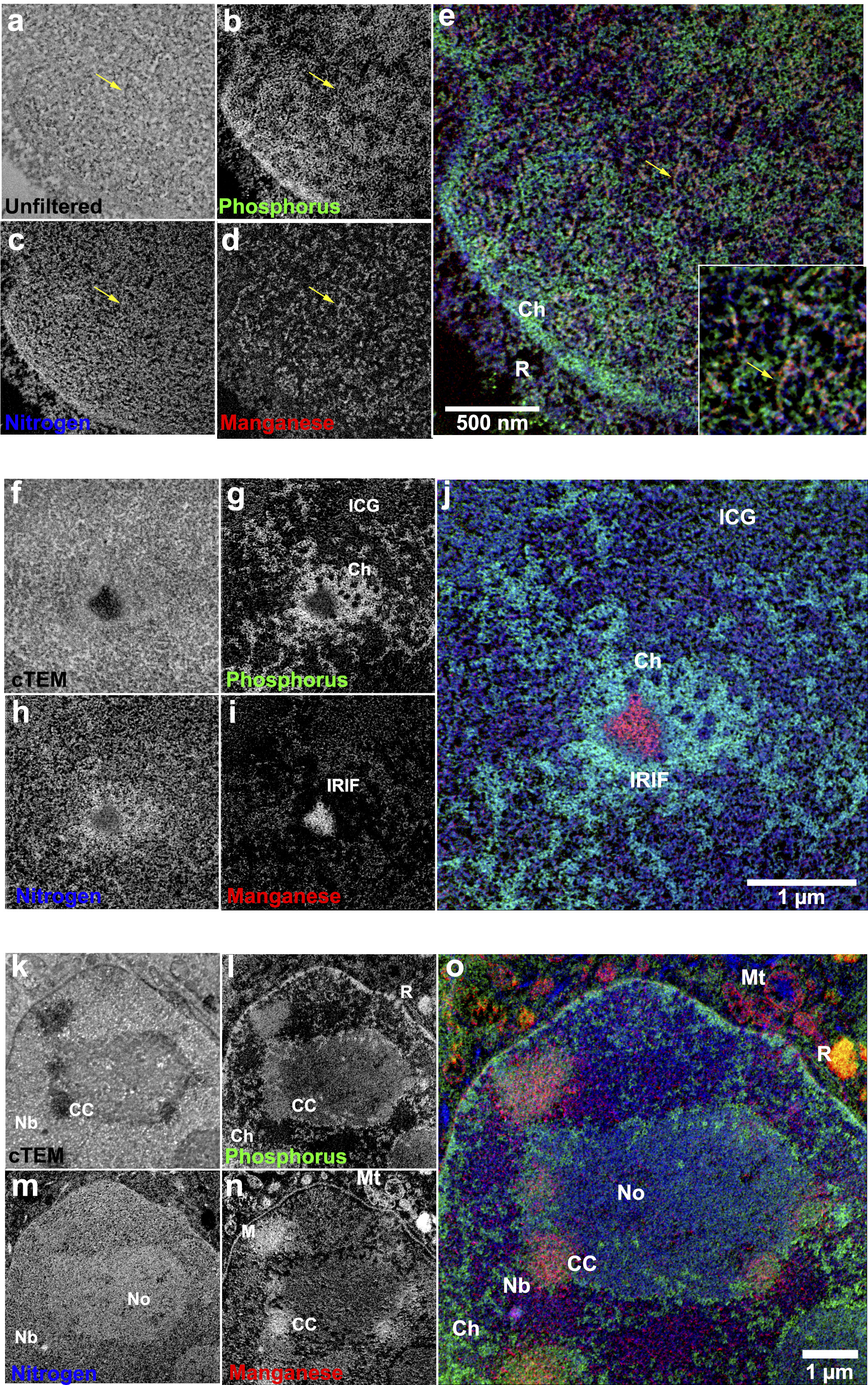

Multichannel Correlative Imaging Reveals Nanoscale Organization of Nuclear Compartments

Booth et al.

Significance: Understanding the ultrastructural organization of the cell nucleus has been limited by the inability to simultaneously visualize multiple molecular components at nanometer resolution. This technical tour de force presents a novel correlative imaging approach that combines super-resolution fluorescence microscopy with multi-color electron microscopy (EM) to achieve unprecedented visualization of nuclear architecture.

Using energy-filtered transmission electron microscopy (EFTEM) with elemental mapping, we developed a method to simultaneously detect multiple markers in the same sample, revealing the precise spatial relationships between chromatin, DNA repair factors, and nuclear bodies at the nanoscale. This approach enabled us to discover that DNA repair factors are not randomly distributed but are organized into distinct sub-compartments within repair foci. These findings challenge existing models of nuclear organization and provide a powerful new tool for investigating the structural basis of genome function. The methodology has broad applications for studying any nuclear process where spatial organization is critical.

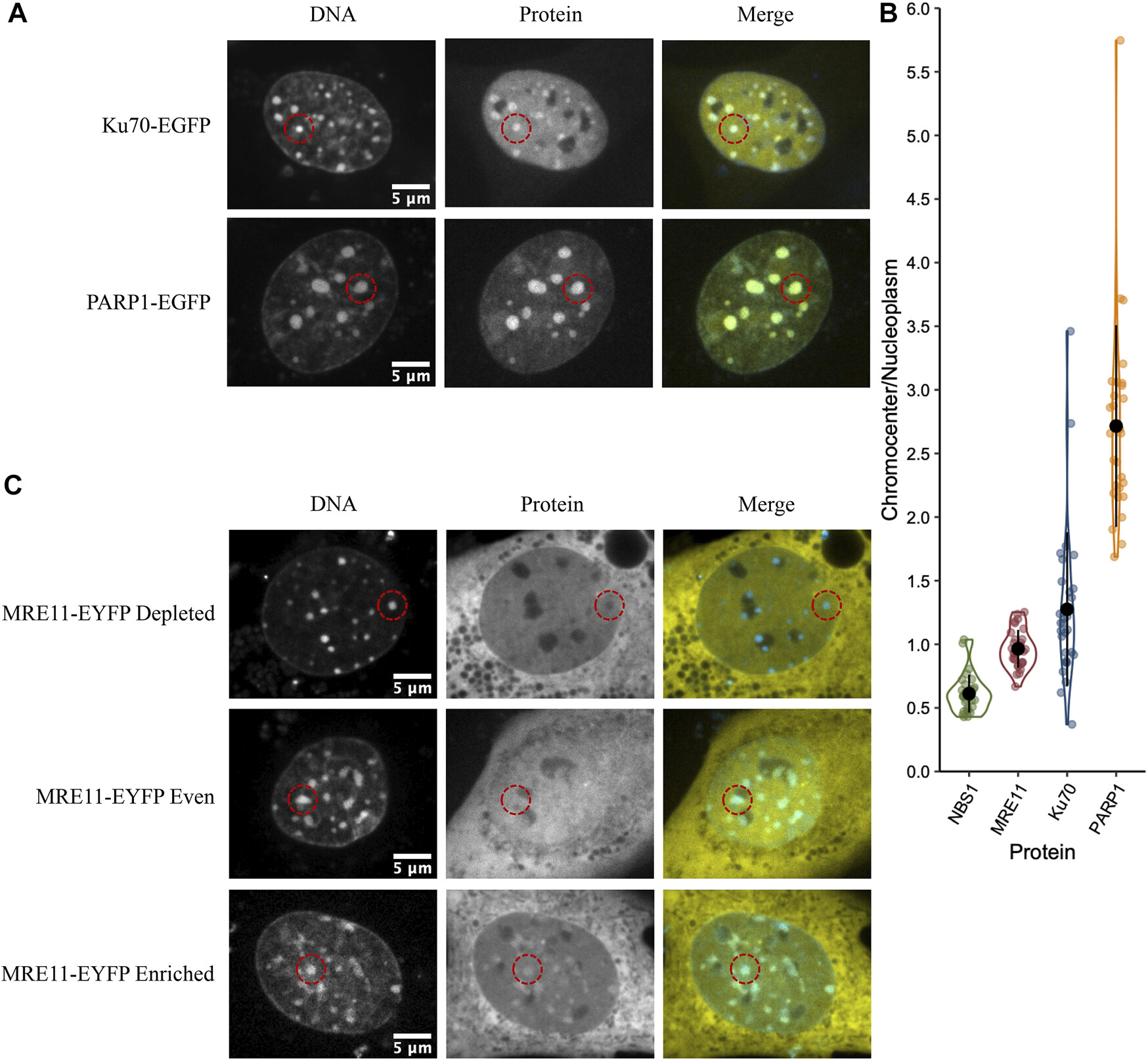

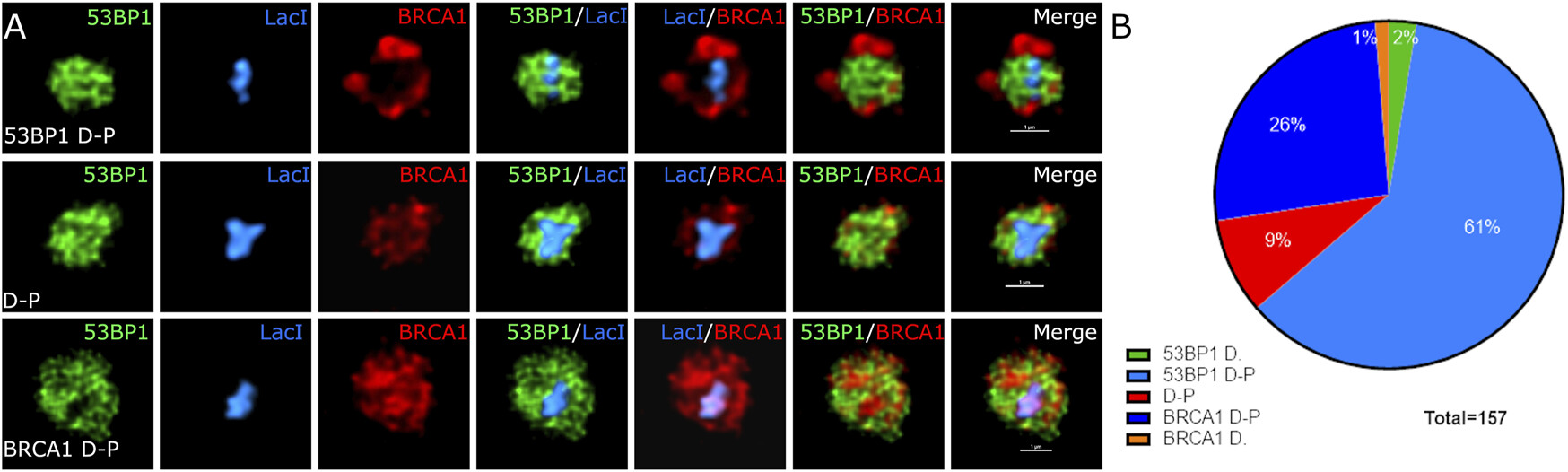

Sub-compartmentalization of DNA Repair Foci: Spatial Organization of Repair Factors at Sites of DNA Damage

Abate & Hendzel

Significance: DNA double-strand breaks (DSBs) are among the most dangerous forms of DNA damage, and cells respond by recruiting hundreds of repair proteins to damaged sites, forming microscopically visible "repair foci." However, how these proteins are organized within foci and how this organization influences repair pathway choice has been unclear.

Using advanced super-resolution microscopy and quantitative image analysis, we discovered that repair foci are not homogeneous structures but contain distinct sub-compartments where different repair proteins are spatially segregated. Specifically, we found that 53BP1, a key regulator of repair pathway choice, forms a core domain surrounded by regions enriched in factors promoting homologous recombination. This spatial organization creates distinct microenvironments that influence which repair pathway is ultimately employed. Understanding this sub-compartmentalization provides crucial insights into how cells make the critical decision between error-prone and error-free repair mechanisms, with important implications for cancer susceptibility and therapy resistance.

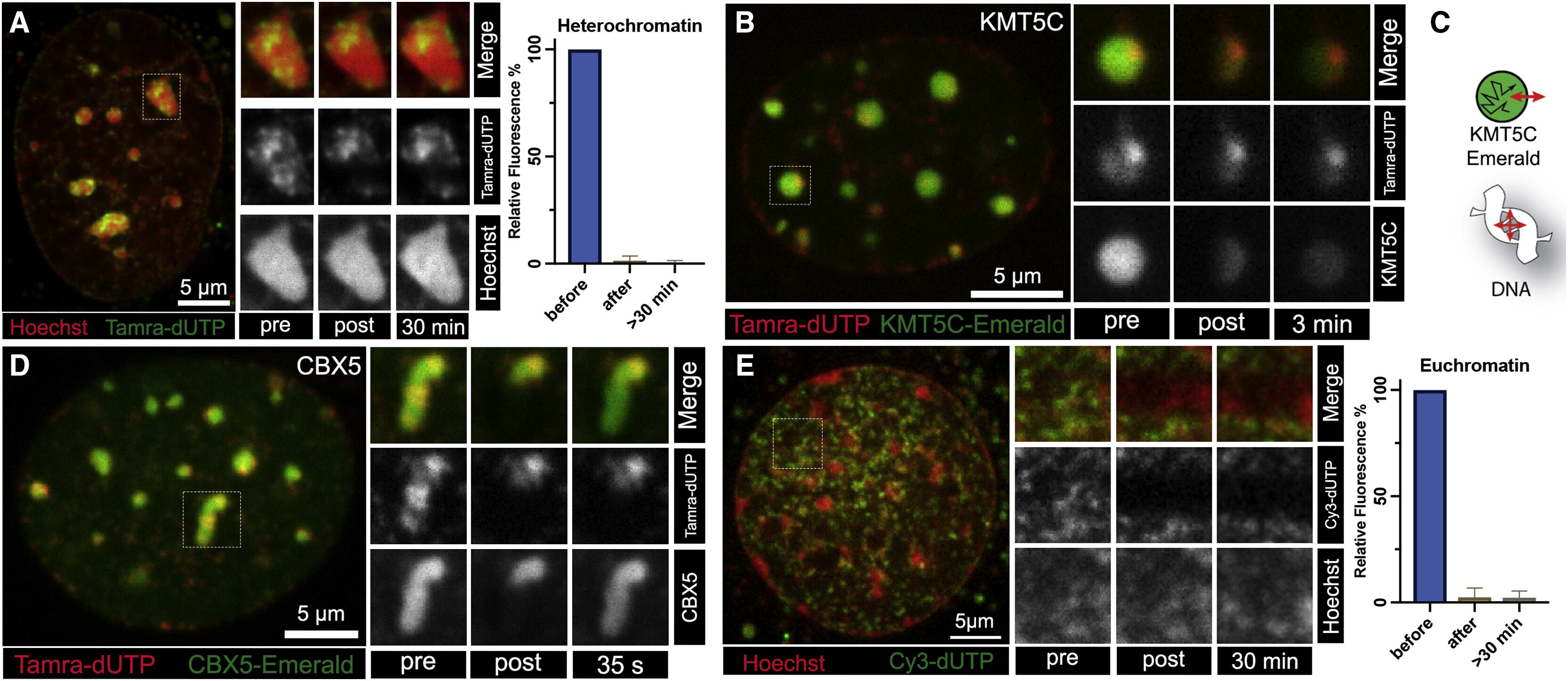

Dynamic Accessibility of Heterochromatin to DNA Repair Factors: Implications for Genome Stability

Roemer et al.

Significance: Heterochromatin is the densely packed, transcriptionally silent portion of the genome that was long thought to be relatively inaccessible to cellular machinery. This poses a significant challenge: how do DNA repair proteins access and repair damage within these highly compacted regions? This study addresses this fundamental question.

Using a combination of laser micro-irradiation to induce localized DNA damage and live-cell imaging with fluorescently tagged repair factors, we discovered that heterochromatin undergoes dynamic, transient changes in compaction that allow repair protein access. Remarkably, different repair factors exhibit distinct kinetics of heterochromatin penetration, with some accessing damaged sites almost immediately while others show delayed recruitment. We identified specific histone modifications and chromatin remodeling complexes that regulate this accessibility. These findings reveal that heterochromatin is far more dynamic than previously appreciated and provide mechanistic insights into how cells balance genome protection with the need to maintain chromatin organization. This work has important implications for understanding mutation patterns in cancer genomes.

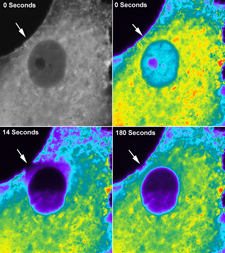

The Solid Phase of Nuclear Chromatin: A Paradigm-Shifting Discovery

Strickfaden et al.

Significance: This landmark publication in Cell, one of the world's most prestigious scientific journals, fundamentally changed how we understand nuclear organization. For decades, chromatin was assumed to behave as a liquid or fluid within the nucleus. This study overturned that paradigm by demonstrating that chromatin actually exists in a viscoelastic gel-like state.

Using innovative biophysical approaches including fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP), particle tracking, and polymer physics modeling, we showed that chromatin forms a network with solid-like properties. Individual chromatin fibers are highly constrained in their movement, yet the overall structure can deform like a gel. This discovery has profound implications: it explains how the genome is organized without membrane-bound compartments, how nuclear processes can be spatially regulated, how mechanical forces are transmitted through the nucleus, and why certain molecules can access DNA while others cannot. The findings force a complete re-evaluation of all DNA-templated processes including transcription, replication, and repair. This work has been widely cited and has catalyzed a new field investigating the physical properties of nuclear organization.

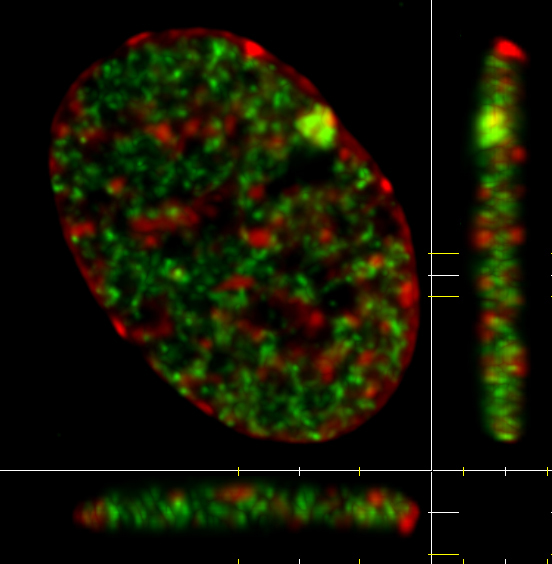

Research Imagery

Advanced microscopy techniques reveal the intricate world of cellular structures and nuclear organization in cancer research.

Actin Filament Structure

GFP-Labeled Cellular Components

3D Nuclear Structure Projection

Research Impact

The work of the Michael Hendzel lab has reshaped the scientific understanding of genome biology. The 2021 publication in Cell demonstrating that chromatin behaves as a viscoelastic gel overturned a long-standing assumption and forced a re-evaluation of how all DNA-templated processes occur. This fundamental discovery has broad implications, from drug design to gene therapy, and garnered significant media attention.

Another major impact came from the lab's 2015 Nature Cell Biology paper identifying the critical role of the RNF138 enzyme in DNA repair. This discovery solved a key puzzle in how cells regulate repair pathway choice and identified a potential biomarker for cancer prognosis and a new target for drug development. Hendzel's body of work, which has been cited over 20,000 times, highlights the profound influence of his research.

Paradigm Shift

Discovery that chromatin behaves as a viscoelastic gel, fundamentally changing understanding of nuclear processes.

Therapeutic Target

Identification of RNF138 enzyme role in DNA repair provides new biomarker and drug target opportunities.

Research Influence

Over 20,000 citations demonstrate the foundational impact of research on the scientific community.

Recent Publications

Chromatin Behaves as a Viscoelastic Gel

Journal: Cell, 2021

Landmark discovery demonstrating that chromatin exists in a gel-like state, fundamentally changing understanding of nuclear organization and DNA accessibility.

RNF138 Regulates DNA Double-Strand Break Repair Pathway Choice

Journal: Nature Cell Biology, 2015

Critical discovery identifying RNF138 enzyme's role in removing barrier proteins from DNA breaks, promoting accurate repair mechanisms.

Nuclear Organization and Gene Expression Regulation

Research Focus: Epigenetic regulation and chromatin structure

Investigation of how nuclear architecture affects gene expression and cellular function, with implications for cancer therapy development.